from College Humor

The

Eighty-Seven Napoleans

by Ellis Parker

Butler

As far as I know, the truth about the eighty-seven

Napoleons has not been told up to this time, and I would not say

anything about it now if some of the stories that are appearing in

the press were not such awful lies, their sole object seeming to

be to cause laughter among those who will laugh at anything, no

matter how estimable. Mr. Pinner, himself, who is hard boiled,

agrees with me that I owe it to my public to give the facts.

"Mr. Pipps," he said to me only this morning, "you ought to

write out the full story of the eighty-seven Napoleons. You owe it

to yourself. Do you see what they are doing to you?"

He then showed me the disgusting article in this morning's

Sunday newspaper entitled, all across the page, "'Pipp! Pipp!'

Said the Eagle," in which some poor halfwit who had nothing better

to do tried to make me seem ridiculous to the readers of the

paper.

"Mr. Pinner," I said, "this is going a little too far. My duty

to my public is a sacred trust and I so consider it. I hesitate to

stoop to the lowness of newspaper controversy, but no sacrifice is

too great for me to make for my public. It is my duty to my public

which urges me to write out the whole truth."

"And I can get real money for it; don't forget that, Pippy,"

said Mr. Pinner, who is, as he often remarks, a hard-boiled

egg.

I will say to begin with that for quite a few years before I

came to Hollywood I was in the book, stationery and hammock

business in Riverbank, Iowa, where I was born, but that I was less

and less satisfied each year because I knew I was meant for

greater things, and the book, stationery and hammock business in

Riverbank would never have satisfied Napoleon Bonaparte.

Although it had been the rude habit of my boyhood companions to

call me Runty Pipps or, more simply, Runt or Runty, by the time I

was twenty-one almost everyone in Riverbank was calling me Bony, a

pleasant recognition of my likeness to the great Emperor of the

French, others calling me Nap or Polly in short for Napoleon. Many

times at local affairs I would hear the cry, "Hey, Bony! Give us

Napoleon!" or, "Say, Polly, do your stuff!" And I would then arise

and place my hat on my head in the Napoleonic way, put my hand in

my chest and frown, and cries of "Atta-boy, Polly!" and "Hot dog,

Bony!" would arise on all sides, many laughing from the pure joy

that is the result of observing an exemplification of perfection

in art.

Thus my resemblance to the Little Corporal amazed and

astonished all, but there was one matter of which I never spoke,

keeping it treasured in my own breast as too sacred to be made a

matter of common conversation. I refer to the fact that was

instantly seen by Princess Elkah-noha when she visited our

town.

I was then thirty-eight years old, and although I wore only my

plain business suit, Princess Elkah-noha uttered a little cry of

delight the moment I had paid her five dollars and she had looked

at my palm.

"Mr. Pipps," she said, "nothing is concealed from me, and

although what I am going to say may surprise you, it is none the

less a fact. You are Napoleon Bonaparte. I do not mean that you

resemble him in face, form and feature, although that is true,"

she said. "I mean you are the great Napoleon Bonaparte,

himself."

"Well," I said, "I have been suspecting that for quite some

time."

"You would," the princess said, looking at my hand again. "I

see a Josephine in your palm, and I beg you to be true to her, for

she is your star and the Ego of the Empress of the French has

taken its abode in her. She is a blonde -- is that right?

Beautiful yellow hair --"

"You might call it hair in a poetical way of speaking," I

admitted, "but probably what you mean to say is feathers."

"Yes, of course," she replied, after looking at me steadily for

a few moments. "What is she, a chicken?"

"She is a canary bird," I explained.

When I reached home I went at once to Josephine and stood

before her cage.

"Josephine," I said, "I will probably have to give up this

comfortable room and sell out my book, stationery and hammock

business before long, because the world will be calling me and I

must seize the opportunity when it comes, but I want you to know

that even if for a moment reasons of State make it seem best to

part from you, I shall not do so because you are my star."

The opportunity for bigger things came sooner than I expected.

Less than a week later I picked up a newspaper and under the

heading, Random Reelings, I read these words:

"Glittering Films has bought the rights in James Melton

Meevick's best selling novel, Malmaison, and will film it

as a two million dollar production under the title, Napoleon's

Cutie. Those who remember Glittering Films' great Lincoln

masterpiece, The Man from Sangamon, and the dozens of

Lincoln films that followed it, will look for a flood of Napoleon

films as a result. Doris Delight has been signed to star in the

Glittering Films picture, and a man resembling Napoleon is now

being sought for the part of the Little Corporal."

Two days later I sold the stock of my book, stationery and

hammock store at auction and telegraphed to Glittering Films,

"Sign no Napoleon until I arrive. Leaving Riverbank tonight,"

signing it Arthur J. (Napoleon) Pipps, and took the train for

Hollywood.

While I waited at Kansas City for the porter to dispose of my

suitcase, I looked to see who was to occupy the compartment with

me, and my suspicions were instantly aroused. I do not mean to say

that my fellow passenger, who was a sawed-off little man, would

have deceived anyone who really knew anything about Napoleon

Bonaparte, but I guessed from the way he kept his hand stuck in

the breast of his coat, and frowned, that he thought he resembled

the hero of October, 1795.

"By the eagles of the Guard!" he exclaimed when he looked up.

"Another one!"

"What do you mean by that?" I asked rather haughtily.

"What do I mean by it? You're going to Hollywood, aren't

you?"

"Yes," I said, "Hollywood is my destination. What of it?"

"You make eight, that's all," he replied. "Eight Napoleons on

this one train, unless some more got on at Kansas City. What have

you got in that cage, an eagle?"

"This is Josephine, my canary," I told him.

"Two of them up front have cats," he said, "and another has a

lady dog in the baggage car, and the Napoleon in the car behind us

has a Josephine cow, but he left her at home. I did not bring my

Josephine, either."

"Why not?" I asked.

"Well, I'll tell you," he said. "I didn't think it was safe --

she's a goldfish."

I looked at him to see if he was joking, but he seemed quite

serious, and I soon discovered that he was a very pleasant

companion. His name was Utterbury, and he introduced me to the

other Napoleons on the train -- there were twelve when we left El

Paso.

As soon as we arrived, I went to the hotel I had been told was

desirable, and the clerk handed me a pen.

"Another Napoleon?" he said pleasantly. "Yes, sir. We can give

you a nice room on the eleventh floor. We are reserving the

eleventh floor for Napoleons. Boy, show Mr. Napoleon to Room 1137.

What have you got in the cage, a parrot?"

"It is a canary bird," I told him. "It is a female and does not

sing."

"Right! We don't allow parrots, but you can keep Josephine in

your room," he said.

As soon as I had tidied myself and given Josephine fresh seed

and water, I asked the way to Hollywood and the Glittering Films

studios, but on the studio gate I found a placard reading: "Notice

to Napoleons: Glittering Films will interview no Napoleons until

nine a. m., March sixth. All Napoleons will apply at gate five on

that date."

I was turning away, when a snappy little one-seated car pulled

up at the curb and a young man hailed me.

"Hello, there, Napoleon!" he called. "Come you here; I want

speech with you."

I walked over to him, and he looked me up and down without

getting out of his car.

"I've seen worse," he said. "Put your hat on crossways. Stick

your paw in your bosom. Look frowny, please. Boy, you're not bad.

You might have a chance. Who's handling you?"

"I don't know what you mean," I told him.

"Ye fishes! The Babe in the Woods doubling as N. Bonaparte! I

mean, who is your agent? Who is your representative, handler,

leader, boss, contract-getter, boomer? But I see you haven't got

one. Give me your hand. Now you've got one."

He took a card from his pocket and handed it to me.

"That's your agent's name," he said. "Joseph Pinner, J. G., and

the J. G. stands for Job Getter, and believe me! Hop in here and

we'll chin-chin. Do you smoke? No matter, I only wanted to borrow

a cigarette. What's your name, Nappy?"

I told him my name, and he drove the car very rapidly for two

blocks and then stopped it.

"Arthur," he said, "the only way to get a job here is to have

an agent, and he's got to be hard boiled. I congratulate you,

Artie; I'm so hard boiled I crack the concrete when I fall. Oh,

boy, you're lucky!"

"Am I?" I asked.

"To get me, Artie," he said. "I just stung Stupendous Studios

to death and got Susannah Sunshine a three year contract, and

that's how I'm free. I said to myself, 'Joe, there'll be a line of

Napoleons a mile long -- go grab one.' You certainly are in luck.

Do you smoke? 'S all right, Art. 'S all right. Lotta men

don't."

"Don't mind my talk, Pippy," he said. "It don't mean a word. I

think best when my mouth is open. Pip, old boy, if you hadn't met

me, you would have been lost in the crowd. This ville is fair

reeking with Napoleons. Now, what to do?"

He started his car, and when we stopped he seemed to have come

to some decision.

"Art," he said, "I'll have to look around and size things up

and make a noise like a press agent. We've got to get Glittering's

eagle eye turned toward you -- and there's an idea. Eagle! Have

you got an eagle?"

"I have a canary bird," I said.

"'Napoleon Arrives with Canary Bird,'" he said. "Won't do,

Nippy. Nev' mind. Joe Pinner will think of something. Are you

married? 'Napoleon's Star Is Beautiful Wife.'"

"I am not married," I explained. "My Josephine is my canary

bird."

"Ouch!" Mr. Pinner exclaimed. "Ain't that terrible! Listen,

Art, you'd better go to your room and lock yourself in until I

come for you. Do that for your Joey, will you? And listen, please,

Art, don't let the canary bird sing. Keep her quiet. Keep her

dark, Art. For my sake."

"Hen canaries don't sing," I said, and he seemed to feel

better. He drove me to my hotel, arranging to see me the next day.

He came about four in the afternoon and when I told him I had not

been out of the room, he seemed much pleased.

"Pippy, my lad," he said, "you sure had luck when you met me.

If you had not met Joe Pinner, you would be lost in the crowd,

because do you know how many Napoleons there are in the county

right now? Seventy-two, Artie. Now, what are you going to do

next?"

"I do not know," I told him. "Am I going to send for some

cigarettes for you?"

"No, Pippy," he said, lighting a cigarette to show me that he

had some. "You are going to organize. You are going to slap

yourself on the knee and cry, 'By George! I will organize the

Napoleon Protective Union, No. One.'"

I think I only stared at him.

"And the reason you are going to organize the Napoleon

Protective Union, No. One, Pipps," he continued, waving the

cigarette at me, "is because it has occurred to you that

practically every town, city and village in America has one or

more men who think they look like Napoleon when they put their

hands in their bosoms and stick their hats on their heads

crossways. In every six clubs out of seven there are men who at

every banquet sit on the edges of their chairs and wait

impatiently for someone to yell, 'Hey, Bill, do Napoleon for us!'

There are hundreds of U. S. Grants and scores of Abraham Lincolns,

to say nothing of three gross of Charlie Chaplins and assorted

lots of T. Roosevelts, G. Washingtons and H. Hoovers, and

scatterings of James G. Blaines, Henry Ward Beechers and Henry

Clays, but the N. Bonapartes are so plenty that the party that

gets their vote carries the national election."

"Yes," I said, "they make me tired -- some of them look about

as much like Napoleon Bonaparte as Little Lord Fauntleroy

did."

"That's the boy!" Mr. Pinner cried enthusiastically. "That's

the spirit! So you are going to say to yourself: 'What if all the

Napoleons come to Hollywood? Where will Napoleon wages drop to

then?'"

"But if I have the job, what will I care?" I asked.

"Art," said Mr. Pinner, "that just shows how lucky you are to

have me. You are one thing, but I am hard boiled. You are thinking

these things so you can get the job. What are you thinking now?

You are thinking that as soon as Glittering Films announced a

Napoleon picture, every other producer thought of doing a Napoleon

picture. You are thinking that there will be a flood of Napoleon

pictures with a lot of Napoleons needed, and that the price of

Napoleons ought to shoot up like a skyrocket, bull market, brisk

demand. So you are thinking, Arthur, that the only way to keep the

price high, avoid ruinous competition and grab the plutocratic

movie kings by the throat is to organize the Napoleon Protective

Union No. One, with union labor cards, a hard boiled walking

delegate and every Napoleon in sight signed on the dotted line. Is

that what you are thinking?"

"Well --" I said.

"Fine! I thought you were," said Mr. Pinner, putting on his

hat. "'Napoleon Pipps Organizes Union of Bonapartes.' I'll have a

costumer here at nine thirty tomorrow and a photographer at ten.

Ah -- where can you hide Josephine?"

"In the bathroom?" I asked.

"Fair enough," agreed Mr. Pinner. "Keep her dark, Pippy. You

know, this is going to be big; this is going to be swell. And see

no one else, Arthur."

When Mr. Pinner came the next morning he was in what I believe

is called high feather, although I do not know exactly what it

means.

Pipps, he said, looking me over as I took a Napoleon pose in

the costume I had been furnished, "you're the stuff! If you don't

look more like N. Bonaparte than Abe Lincoln ever did, I am a half

portion of chile con carne. Everything is going jake, Artie. The

morning census of Napoleons shows eighty-seven on the list, and

the organization meeting will be held in Room Seven B downstairs

at nine p. m. tomorrow night. Already you have received promises

from seven Napoleons to be there."

"I have?"

"Through Joe Pinner, your aide, as per your instructions," my

lively friend said. "And what are you saying to me now,

Napoleon?"

"What am I?" I asked him.

"You are saying: 'Pinner, obey my orders. Get busy and see the

rest of the Napoleons. March!' That is what you are saying,

Napoleon. Sire, I obey."

With that he rushed off again, and except for a word by

telephone every few minutes I heard no more from him until the

next evening. About half past eight o'clock he came to my room,

interrupting me as I was feeding Josephine a bit of lettuce with

my fingers.

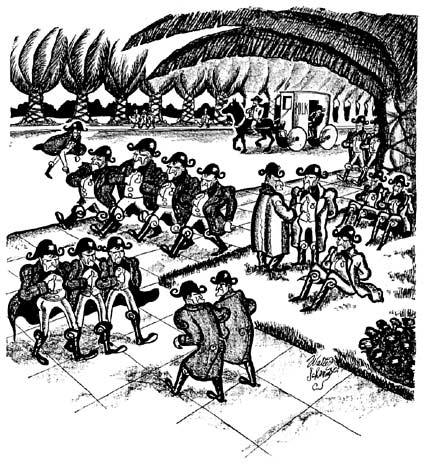

We then went out to the elevator where we found a crowd of

Napoleons waiting to go down to Room Seven B. They looked at me

with frowns, being themselves dressed only in ordinary clothes,

but I pushed through them to the elevator door.

"The next car, please, gentlemen," I said. "This is reserved

for your Emperor," for that was what Mr. Pinner had told me to

say, and no doubt he had instructed the elevator boy, for as soon

as I was in the car he slammed the door and started the car

downward.

In Room Seven B I found a good number of the eighty-seven

Napoleons, and the rest soon arrived. Mr. Pinner immediately took

the chair at the table at the head of the room and rapped sharply

for order.

"I'm going to ask Mr. Utterbury, one of our most distinguished

Napoleons, to act as secretary of this meeting," he said, and Mr.

Utterbury arose and went to the table, taking the vacant seat

beside Mr. Pinner. It was easy to see he was pleased to be thus

honored.

"As for chairman," Mr. Pinner then said, "I will myself retain

the chair, being perhaps better acquainted with the Napoleonic

situation than anyone present."

This was the cue he had given me, and at the word "present," I

walked forward and, pushing in beside him, took the gavel from his

hand.

"Fellow Napoleons," I said in a loud voice, "none but the

Emperor presides here."

For a moment there was silence and then one or two applauded,

and in another moment Room Seven B was resounding with the

clapping of hands. Mr. Pinner got up out of the chair and I seated

myself.

"To work!" I cried. "Utterbury, read the constitution and

by-laws."

"I haven't any, Mr. Pipps," Utterbury said, and I drew the

constitution and by-laws from my pocket and handed them to him. He

read them just as Mr. Pinner had written them.

"Before we vote on the adoption of the constitution and by-laws

as read," a Napoleon in the middle of the room said, "I desire to

offer an amendment to Section One, Article One of the

Constitution, which provides that the temporary chairman of the

organizing meeting shall be permanent president of the Napoleon

Protective Union No. One. It is my opinion --"

"You're out of order," I said, bringing down my gavel. "I have

already adopted the constitution and by-laws."

"Don't we vote?" a Napoleon asked. "Usually at these meetings

the --"

"I am the meeting. If I want a vote, I will vote," I said,

frowning to right and left. "Is there any other business to come

before the meeting?"

There did not seem to be. The dues had been stipulated by the

by-laws, the constitution provided that no Napoleon should sign a

contract with any motion picture concern until the contract had

been approved by the permanent president. As a matter of fact, no

Napoleon could do much of anything but brush his teeth without

permission of the permanent president. No one seemed to be able to

think of anything else for the meeting to do and, as Mr. Pinner

had instructed me, I now motioned him to come to me and he did. We

stepped far enough aside to be beyond Mr. Utterbury's hearing.

"Pippy," he said, "this was great stuff and you will get two

columns in tomorrow morning's papers, or I'm a wooden nutmeg.

'This Napoleon Real Autocrat -- Pipps Rules with Iron Rod.' That

is where little Joe Pinner knows his psychology; any bunch of

anything of one sort is a bunch of sheep, and the one that is

different can boss them. A room full of imitation Julius Caesars

would sit thinking, 'I must not forget to look like Julius

Caesar,' and a rabbit could walk away with them. Am I right?" Then

he bowed low and said so all could hear, "Yes, sire, I will tell

them."

With these words, Mr. Pinner walked in front of the table and

raised his hand.

"Gentlemen Napoleons of Napoleon Protective Union No. One," he

announced in a loud voice, "I have been commissioned by your

permanent president to declare in his name an event which you will

all welcome with delight. In honor of his announcement of his

promulgation of the constitution and by-laws, and the creation of

the Napoleon Protective Union No. One, your president has decreed

that the staunch yacht, Orange Blossom, be chartered to start on

an excursion to Catalina Island, March fourth at nine a. m. The

day will be spent in pleasure, visiting the beauties of sea and

shore, observing the bathing beauties disporting in the waves, and

so on, but important business meetings will be held going and

coming, the yacht being less accessible to prying ears than this

room."

"The meeting is adjourned," I said as soon as the cheers had

died down, and Mr. Pinner shouted, "Keep your places until the

president leaves the room!" And with Mr. Pinner before me, I

walked out of Room Seven B.

"Well, Pippy," Mr. Pinner said when we were back in the room,

"I'll say that went off fine. You behaved like a good little boy,

and I think the yachting party is going to be a great

success."

"Who is going to pay for it?" I asked.

"The Napoleon Protective Union No. One, of course," said Mr.

Pinner. "That is provided in the constitution, anything decreed by

the permanent president being paid for out of the treasury. What

is the use of being a Napoleon if you can't be one once in awhile?

Of course, there will be some kicking when they land on St.

Helena."

"St. Helena?"

"My little joke, Pippy," Mr. Pinner laughed. "I must have my

fun and I never had a chance to maroon eighty-six Napoleons at one

time before. Of course, you saw what I was up to."

"I don't know what you are up to even now," I told him.

"What you don't know won't hurt you," he informed me, "but you

need not do much packing for the trip to Catalina, because you are

not going. And if the eighty-six Napoleons want to change linen,

they had better take some along because it may be quite a few days

before they get back to Los Angeles."

"You are going to kidnap them!" I exclaimed.

"No, no! Not I, Pippy, you are going to kidnap them. The Orange

Blossom is going to break her rudder chain or something, that's

all, and they will not get back until after March sixth, the day

all the Napoleons are to be interviewed. You will be the only one

there, Artie."

"Mr. Pinner," I said, "you may think this is a very clever

scheme, but it will not work and I will tell you why. Glittering

Films knows there are eighty-seven Napoleons in Los Angeles, and

if I appear alone, they will simply say the date has been

postponed."

"Pippy," said Mr. Pinner, "sometimes when you express your

opinions, I can almost understand why you had a Waterloo when you

were here before. Have you ever heard of anything mightier than

the sword?"

"The pen is mightier than the sword," I quoted.

"If you make that, 'The headline is mightier than the sword', I

may believe you," Mr. Pinner grinned, and it proved that he was

right.

The morning after the organization meeting, Mr. Pinner came for

me in a superb open car of a light rose color with pale moss

colored upholstery, and, wearing my uniform, I was seen in that

car every day until March fourth. On that day I was not seen at

all, and the Orange Blossom was forced to sail without me, nor was

I seen on the fifth. On the sixth, I appeared at gate five at the

exact moment when Napoleons were welcome, and I was the only one

to appear. Mr. Pinner, of course, was with me, and we were told to

see Mr. Hoskins, the casting director for Napoleon's

Cutie.

Mr. Hoskins looked up when we entered, and greeted Mr. Pinner

with: "Hello, Joe. Have a seat over there till some of the other

Naps get here -- I'll run them off in bunches." He went on with

his work, but almost immediately a beautiful young lady entered

and Mr. Pinner was on his feet instantly.

"Hello, Doris," he said. "I want you to meet the man I have

picked to do your Napoleon. Mr. Pipps, this is Doris Delight."

The superb creature looked at me.

"He's not so poisonous at that," she said, and went to speak to

Mr. Hoskins.

"Hot dog!" Mr. Pinner said in a whisper. "Did you hear that?

Artie, things are coming our way! She fell for you at the first

peek."

"She didn't seem so very enthusiastic," I said, but Mr. Pinner

grinned.

"She was enthusiastic enough to cost Glittering Films an extra

twenty thousand dollars," he said. "And now wait until you hear

Hoskins."

With that he went over to Mr. Hoskins' desk and stood beside

Miss Delight. She gave him what I thought was a crushing look, but

Mr. Hoskins asked him, "Well, what now?"

"I just thought perhaps Miss Delight was waiting to look over

the other Napoleons, Hosky," Mr. Pinner said, "and that I could

save her some time, because none of the other eighty-six Napoleons

will be here today."

"What does that mean?" Mr. Hoskins asked.

"My Napoleon here just tells me," said Mr. Pinner, giving Mr.

Hoskins a wink, "that he hired the Orange Blossom and put the

whole gang on board and sent them somewhere day before yesterday.

They won't be back for a day or two. Regular Napoleon stuff, hey,

Hosky? 'Kidnaps Eighty-Six Rivals.' Can you see the headlines? 'He

Got the Job.' When eighty-six sore Napoleons get back to town,

will there be noise?"

"How does he photograph, Pinny?" Mr. Hoskins asked, looking at

me.

"Like Douglas Fairbanks," Mr. Pinner boasted, "only

better."

"We've got to give these other Napoleons the once over, Pinny,"

Mr. Hoskins said. "We've sort of promised that. How much is your

man going to sting us for?"

Mr. Pinner whispered in Mr. Hoskins' ear, and Mr. Hoskins made

a sour face before he grinned.

"What do you think of him, Doris?" he asked Miss Delight, and

she looked at me again.

"Not so venomous, Hosky," she said, and Mr. Hoskins took the

contract Mr. Pinner had evidently prepared.

"It's like I tell you, Pinny," he said. "I can't sign anything

till we look at the other goops. The old man wouldn't let me. But

I've had an eye on your boy. He gets the publicity. He knows the

Napoleon job. Or if he don't, somebody does."

When the eighty-six Napoleons returned from their voyage on the

Orange Blossom, the headlines in the newspapers were all that Mr.

Pinner could have wished, if not more, and if there were any

newspapers in America that did not receive the story from their

own correspondents or press associations, the Glittering Films saw

that they were supplied with the full details as soon as my

contract was signed.

In justice to Mr. Pinner, I will say that it was the Glittering

Films' young man who sent out the article saying I made a pet of a

golden eagle I had captured with my own hands on a mountain cliff,

and that he did this without my knowledge, but since I have been

held up to ridicule in a vile piece of so-called humor that

pretended to discover that the eagle was only a female canary

bird, I have written this so that all may know the truth about it.

I never claimed that Josephine was an eagle. The story that I did

was the work of a jealous member of the eighty-six Napoleons, all

of whom I am now free to say are mere imitations.